The status of American comics pioneer and creative fount Jack Kirby slipped badly in the space of a few short years in the early 1970s. His highly successful resume at Marvel had led DC to promote his defection to them as their greatest triumph, but their support quickly waned. There was some resentment directed at Kirby by people who were highly placed at DC, that contributed to making his time there uncomfortable. For instance, DC’s production manager and excellent colorist at the time, Jack Adler, considered Kirby to be an “egotist.” And, the company was struggling to deal with the fact that reader’s tastes were changing, largely due to the revolution that Kirby had created with Stan Lee. DC’s lack of faith was not not solely with Kirby, though. Many DC books were begun, then rapidly canceled at that time. That DC would ask or allow Kirby to waste his talents on Jimmy Olsen is indicative of the level of taste and sensibility they had going on. The audience was more sophisticated, DC was seen as conservative and staid and they were. In addition, Marvel broke away from the distribution deal they had with DC in 1968 and tripled their production by the mid-1970s, from 20 to 60 titles. After Kirby left Marvel, they flooded the market with reprints of his work. So, there was a deluge of old Marvel Kirby on the spinner racks, drowning out his few new DC books.

For their part, DC used Kirby as Marvel had. He initiated multiple titles, each full of ideas and characters that could and would be later exploited, but all of his books except for Kamandi were canceled and by the end, DC expected him to invent first issues for series concepts for a title called 1st Issue Special. He did not renew his DC contract, but made an also initially-promoted but ill-supported return to Marvel. By 1978, a dispirited Kirby had retreated from the “snake pit” of Marvel into the television animation industry, where he was well paid for his conceptual efforts and finally got a health plan. However, in making animation presentations, little of what he drew made it to the small screen and in fact few people actually saw his drawings, meaning that neither his storytelling Jones nor his ego were served. So, in 1981 he returned once more to the comic book format, with a pair of titles for the fledgling independent publisher Pacific Comics.

To some, Kirby had fallen far. Captain Victory and Silver Star were the butt of many jokes and disparagements in their time. However, Kirby’s work for Pacific Comics was potent enough to launch the direct market system, which became the predominant structure of comics distribution and began the dissolution of Marvel and DC’s dominance over American comics. He was also concurrently involved in legal battles with Marvel involving his original artwork and it has been alleged that he was the victim of corporate slander and blacklisting. Often cited as evidence of Kirby’s failing powers at the end of his career, the Pacific books are rarely examined, but they can sustain a closer look. They are about freedom, Kirby’s freedom to do comics as he pleases, after a long career of creating to please others. Yes, they are often extreme and inconsistent, but they also offer some awesome pleasures and some of what seems ridiculous is the artist reaching to convey concepts that are beyond his (or perhaps anyone’s) powers of description.

At Pacific, Kirby fully realized his transformation into a proto-alternative comics auteur, as he wrote and drew stories that were free of editorial interference. In Captain Victory, Kirby displays extremes of his personal textual and artistic tics that might not have survived an editor’s scrutiny, for better or worse. His writing and art can be obtuse and is sometimes parodic of his own stylistic tropes and of what became of his prior work, now out of his control. Some of the sloppiest panels he ever drew are in direct proximity to panels as good as peak work on Thor. Kirby’s writing veers wildly from unbelievable silliness to heartbreaking irony. There is much that it would be deceptive to praise, but there are also moments that offer an unrestrained expression of his magisterial vision. One has the feeling that Kirby owes nothing, but is still giving.

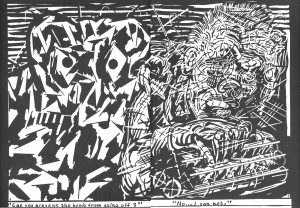

In Jack’s late work a different set of priorities emerge that diverge from the aims of his earlier efforts. Kirby’s drawings often seem to be as much about the nature of his marks on paper as they are about the narrative, which further confounds matters. Marks that denote abstracts like movement and energy take on the same weight as those representing bodies in real space, light becomes patterns which interlock in a dialogue with marks and patterns in other panels. The pages are drawn small, so the work cannot have the sweeping space of his great twice-up original Marvel masterworks. Kirby’s own physicality has diminished and so he does not draw the lithe, bulging, hyperenergized forms that pressed the borders of the pages in his prime, now he makes stressed, compressed figures that sometimes seem to barely hold together, crushed into hermetic tableaux. It is the comic book as an encrypted and encoded personal illumination.

As can be seen throughout Kirby’s career, the ink interpretation of his drawings is largely dependent on the ability of the inker to understand the principles of volume, space and light that are imbedded in his deceptively simple lines and shadings. If an inker does not understand, for instance, that the interior “blobs” on a Kirby figure are meant to represent lighting from multiple sources, they will ink them as arbitrary abstracted marks. Artists like Joe Sinnott, Frank Giacoia, Syd Shores and even Vince Colletta are on solid enough ground in drawing and composition as pencillers themselves to reinforce and even enhance the structural solidity and linear nuance of Kirby’s drawings.The accomplished Mike Royer inked the initial pages of Captain Victory, that had been completed years before as a proposal for what would have been an early graphic novel. These were split between the two first issues. Royer’s own style is essentially flat and cartoony, but he is able to realize Jack’s intent and add a polished, professional sheen. The inking on the newer stories done for the Pacific series is by Kirby’s inexperienced protege, Mike Thibodeaux. All of the inking at Pacific is true to Kirby’s pencils, but Thibodeaux does not have the knowledge and skill of Royer; he traces Kirby’s lines carefully, but often misses the nuance of good drawings or even weakens the structure.

Captain Victory displays furious energy. It is not hard to imagine that Kirby might have seen the contemporaneous work of Gary Panter, that he absorbed some of the structuralism of Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly’s Raw. Kirby often reflected the state of the culture around him, borrowing from popular books and films. He would also reabsorb the influence taken from him by another artist, as he was known to have evolved his work to suit the interpretation of his inkers like Joe Sinnott, or as in Kirby’s appreciation for Phillipe Druillet from his sojourns to Richard Kyle’s well-stocked comic shop. Both Mister Miracle #2 and Hunger Dogs reflect the influence of the in-turn Kirby-influenced Druillet’s ornate borders.

Likewise, the heavily and aggressively cartooned and patterned, nearly abstract linear quality of Jack’s Pacific work has an overtly self-aware surface that seems to me to be similar to that of Panter’s Jimbo.

Panter has not only spoken of Kirby’s impact on his work, it is clearly visible. The fierce, slashing, almost punk energy of both Captain Victory and Silver Star drove me to speculate that the influence was reciprocal, that Kirby had been looking at Panter, when I first saw them at the time. Now, I have not found the smoking gun, in that I haven’t yet been able to place that 1982 cardboard-covered Jimbo in Kirby’s hands. But at any rate, the faithful, flat surface of Thibodeaux is not altogether inappropriate on Kirby’s late efforts and regardless, the young inker does manage some very strong pages and passages.

The first six issues of Captain Victory boast some of the most dramatic and effective coloring that Kirby ever got in comics besides his own, by Steve Oliff. Kirby rarely had sympathetic colorists, nor did he often have control of the coloring. When he did, he was brilliant but he rarely had time to do it. The same rules apply: if a colorist comprehends the space and light in Kirby’s art, they can enhance it greatly.

Oliff’s color is often inspired, but he was replaced by Janice Cohen, who did a fine if standard job. For the final issues Pacific changed over to fully rendered color while they simultaneously experimented with paper stocks, causing a mutating product which made Tom Luth’s late airbrushed efforts appear garish and inconsistent.

The initial 48 pages of Captain Victory were intended by Kirby as a response to the Steven Spielberg film “Close Encounters of the Third Kind.” Dogface Pvt. Jack Kirby could not assume that aliens intrepid enough to cross the galaxies would be any less opportunistic that we humans would be in a similar situation.

He advocated a full defensive mode. He envisioned an attack on Earth by an aggressive species and created Captain Victory as the vanguard of an advanced force that guards the galaxy from such predatory races. Though the lead character resembles two of Kirby’s signature heroes, Thor and Kamandi, he is a less an individual than a soldier tool of an interplanetary governmental body, like Captain Kirk of the Federation but with a harder, dehumanized edge more like the recent series of “Battlestar Galactica.”

“Victory is sacrifice, sacrifice is continuity, continuity is tribulation” is Captain Victory’s mantra. This might relate to the fact that all the characters Kirby created for Marvel Comics were sacrificed by their creator to the corporation to become properties, to be continued by other artists. By making them successful, Kirby was shut out of his creations, time and time again. Kirby places Captain Victory as belonging to the Galactic Rangers, his being is their property. The current version is a clone. He sacrifices himself to the Rangers’ cause by repeat-offending suicide. He dies, but there is no real continuity… when he is killed in combat, his recorded memories are transferred via a “storage unit” to a fresh clone of his body. A new Captain Victory arises, a thing that thinks it is him but is a copy (incidentally, this is also a compelling argument against “Star Trek”-style transport). The moment of the previous incarnation’s death has been erased, so the copy has no memory of suffering, that might give it pause before it re-ups.

The emphasis on characters as properties that is seen in the most prominent comics publishers is entirely deliberate. Conceptual ownership by way of work-for-hire gives the advantage to the publishing corporation and devalues the unique talents of the individual writers and artists who make the work. The producers of the work are considered to be expendable, other writers and artists might do just as well concocting variations of a given set of ideas and also be more malleable to the corporation’s control. Artists who are kept busy retreading concepts created by others are less invested in the work. They might add new characters within the established parameters (disowned as work-for-hire), but have less time to develop properties of their own that they would be invested in (and the corporation will often stick to safe, proven ground and discourage innovation).

Thus, a narrow pool of concepts is tightly controlled, harnessed and milked, an endless serial produced through collective effort to become, the corporation hopes, a “new mythology for our times.” A myth is a construct, not a person. The myth is The Silver Surfer, not Jack Kirby. In a corporation, there can be no individuals—no one person can be responsible for success or failure, there are no ethics involved, the overriding consideration is the profit of the collective of stockholders. But, with the last part of the Ranger’s creed, “continuity is tribulation,” Kirby implies empathy with those souls tasked to continue the adventures of the properties he has lost. They must work hard, to have no autonomy. They are clones of himself, who must endure after he is gone. And, Kirby sometimes rejects continuity in these books, he does not seem to care if there are holes in the story or inconsistencies in his drawings from panel to panel—and nor do I. Finally free of micromanagement, Kirby makes some of the most spontaneous comics of his career.

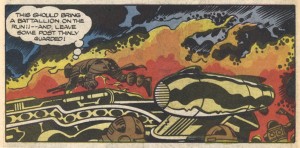

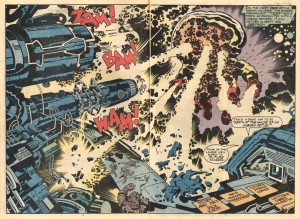

Captain Victory #s 3-13 were drawn in brief bursts, when Kirby could fit them in between his commitments to his animation work, but they still show a high level of conceptual vigor, there are a lot of ideas put forth. To be sure, there are many weak passages, but there are also killer panels and pages and quite a few double-page spreads that rank with some of the finest Kirby ever did. The first storyline extended from the initial novella. Elaborations of the “Bugs” from the New Gods series that yield many fabulous designs which outshine their previous incarnation, the Insectons come to Earth to exploit its resources. They feed on life energy and the bloated bodies of their human victims are stored in fluid “food-channels,” shown to chilling affect in #5.

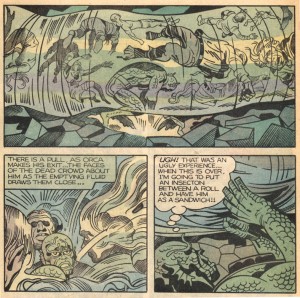

The Rangers waste no time in making a full-on assault on the infestation. Some of the Rangers remind the reader of Kirby’s earlier creations, as in the resemblance of Orca to the Inhuman Triton and Tarin to Kamandi‘s tiger Prince Tuftan, but they are also less individuals than parts of a well-oiled machine, disciplined and equalized in military service. The books are militaristic but it would be a mistake to assume a hardening of Kirby’s humane outlook. Kirby was in the infantry in World War II and did not enjoy the experience. The Rangers’ dialogue is seldom the sort of action patter found in the comics of Marvel and DC, rather Kirby ascribes to them a bizarre mix of poetical expositions of the metaphysical and ethical dilemmas that can be spun from his sci-fi premise, with a sometimes silly and/or anachronistic humor, meant to represent the absurdities that those in dangerous situations indulge to leaven their trauma.

The Insecton “story arc” culminates in the double-sized and stunningly covered #6, a nearly apocalyptic scenario that sees the good guys win but the Captain first partially blinded, then killed yet again to save our planet, in this case through an overdose of life energy by his operation of a giant “drainer” that sucks the enemy’s essence from their husks. The violence in Captain Victory is more “real” than in other Kirby comics, here he shows the consequences.

In the arcs that follow, the stories begin to take on the quality of tales told late at night by an ancient relative with a thick accent—it’s hard to hear or they don’t quite make sense, but a disquieting enormity is felt, a sense of the weight of millennia and of infinite forces outside one’s control. One cannot understand, but one wants to, because it feels important.

The second, four-issue storyline deals with the Wonder Warriors, four disparate villains who obey the dictates of a disembodied Voice, that include the cooly armored Bloody Marion and Finarkin the Fearless, Ursan who decomposes matter with his touch and Paranex the Fighting Foetus, an overt reference to then-contemporary challenges to Roe v Wade spurred by right-wing Senator Jesse Helms. The famously liberal Kirby sidesteps the issue of women’s bodily autonomy entirely as the oversized telekinetic embryo inspires moral qualms in the Captain, who says it is not fair to kill something before it officially exists, despite its aggression and that it is independently free-floating, encased in armor and has already been named.

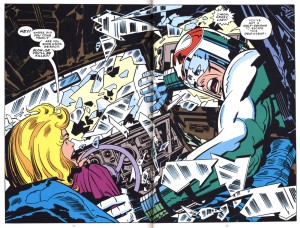

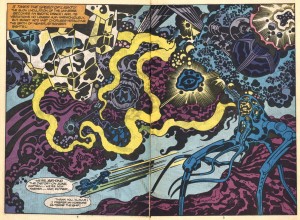

The most cryptically magnificent passages in the series take place in #10. In an incredible spread, the sexually indeterminate pre-being Paranex assaults the Ranger’s dreadnaught. Victory’s concern for the criminal Foetus is revealed as a sham intended to draw out the Voice, who the Captain mysteriously knows, and when it does, they proceed to an unclear endgame.

In language dripping with portent, Kirby has his Captain order his crew to remain passive as he is apparently dragged senseless off into space by the Wonder Warriors. Of course that also is a trick and perhaps an excuse for Kirby to draw more unsettling images of his creations pulled to their doom by floating cubes that have all of the “presence” of Donald Judd’s Specific Objects. They all blow up but Victory is fine, he has sent out a robot of himself and he prepares to explain to his crew his prior knowledge of the Voice.

The final story arc is a flashback spread across three issues; these contain themes seen elsewhere in Kirby’s work: a critique of militarism as evolutionary barometer, as in his extrapolations from Kubrick and Clarke’s “2001”; and the question of “nature versus nurture” that he would later return to for his rejected conclusion to the New Gods, “On the Road to Armagetto.”

Captain Victory #11 shows a literally monstrous side of the hero as he relates with Shakespearean cadence the story of his (original’s) childhood in the court of his cousin Big Ugly, who has horns and multiple mouths. Though Victory is human and so apparently incompatable with his demonic relative, the 8 year old child easily suggests cruelly innovative ways for Big Ugly to conquer the known universe. Ugly and the rest of the royal family are in thrall to the Voice, which is revealed to be that of Victory’s dead grandfather, Blackmass. Victory’s family follow this incorporeal spirit’s foul will and justify their actions to their victims in religious terms. With typical prescience, Kirby makes the kid’s best friend a computer. The child is the instigator of some of Big Ugly’s most heinous actions, yet seems to find it all horrifying/boring. Victory is a precociously talented architect of genocide, but he disassociates and is able to blame his cousin as if the acts are unconnected to him and then has no problem betraying the bond of blood to murder Big Ugly, heralding his coming of age as a soldier.

Cases have been made for possible correspondences of issue #12 with the New Gods saga by John Morrow and other Kirby fans. It depicts the boy as with the aid of his (um, huge) digital pal he destroys his ancestral planet Hellicost (Apokolips) and flees into space, only to crashland on a planet that is home to yet another militant psychopath, Captain Flane, who may or may not be his father.

Flane plays God to the indigenous population, forcing their evolutionary development by facilitating their development of military technology, leading to his own death at the hands of his “students.” For Morrow et al, the issue represents Kirby retaking his creations to give them a more fitting end. They believe that Flane represents Orion and Blackmass represents the ghost of Darkseid. Perhaps, but it also seems appropriate to note that Victory’s future state of serial martyrdom is foreshadowed by Flane’s suicidal manipulations. Victory seems to be the carrier of a murderous genetic package, but Kirby also rejects predisposition to violence with the implication that such an ingenious race as the one Flane corrupted might have used their natural curiousity to more constructive ends, had they been influenced by a less aggressive mentor.

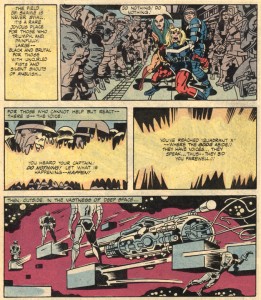

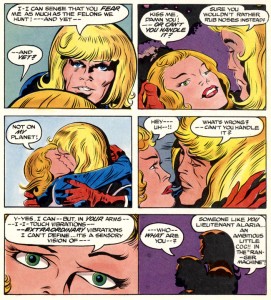

The series ends in a distinct affirmation of the creative power of the artist. In CV #13, Victory cannot act on his clumsy love for his fellow Ranger recruit Lieutenant Alaria. In fact, all of his more individualistic impulses are suppressed and superceded by the demands of his duty.

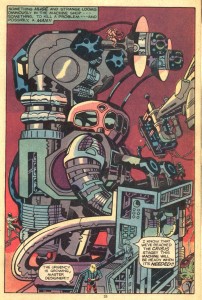

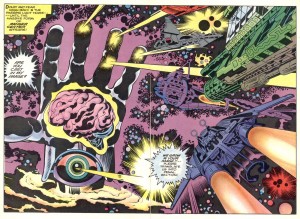

Kirby finally allows Victory to meet his maker, the true “Source:” the hub of the Rangers is depicted as a surreal abstraction of the artist, a humongous floating hand which surmounts an eye and is a container for a brain.

Victory and Alaria are revealed as easily manipulable pawns, to be split up for dramatic purposes or “reassigned” to be given yet “more complex duties.” Flashes of compressed adventures follow the ambitious yet loveless career soldier to Alaria’s death and his Captaincy, as he “achieves the reason for his existence,” that he is a cog in a wheel and also the starring hero of the last Kirby epic. He will not procreate, but be a copy of a copy of a copy etc. He is pre-genericized, the comic is self-aware and takes on the aspect of a loop, we are back where we started and Jack Kirby is done. He has given us a look at our own worst impulses and into the far reaches of his mind.

________________________________________________________

First published on The Hooded Utilitarian

SOURCES

Amash, Jim. Interview with Jack Adler. Alter Ego #56.

Brown, Andy. “In Defense of Our Galaxy.” Monster Island Three. Conundrum Press, 2007.

Lewis, Jeremy. “In Defense of Our Galaxy.” Jack Kirby Quarterly #8.

Taylor, Stan. “Why Did the Fourth World Fail?” The Jack Kirby Collector #31.